Naloxone Leave Behind Programs Spread Across US

With overdoses surging in the wake of COVID-19, more first responders are leaving behind naloxone for faster access.

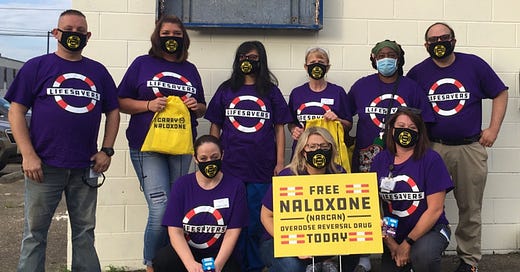

Photo from West Virginia’s pilot Free Naloxone Day, Sep 2nd 2020.

Something rather special and desperately needed is spreading across the country: new programs where EMS are leaving behind naloxone to people who are most likely to save lives or need to be saved.

For over 30 years, first responders have been administering naloxone to people who’ve overdosed on opioids. It’s a newer phenomenon that EMTs and firefighters are equipped and empowered to offer a free naloxone kit to these same patients for potential future use. This phenomenon is catching on as a strategic response to the major surges seen in overdoses since COVID-19 struck.

In Toledo, Ohio, the University of Cincinnati freed up $20,000 for the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department to make sure local firefighters can hand off naloxone before departing an overdose scene. Toledo Council will vote on it later this month.

Toledo Fire and Rescue Department’s EMS supervisor Lieutenant Reed told The Toledo Blade, “Because we respond to all the overdoses that are 911 calls, we have access to these people and we could leave the lifesaving medication of naloxone with those patients that refuse to go to the hospital.”

The idea with Leave Behind programs is that survivors of overdoses are at higher risk of future overdoses, and are more likely to be near other overdose events. Ensuring this group of people carries naloxone means faster access to this antidote in emergency situations where every second counts, and therefore greater chances of survival over the longer haul.

In Michigan, overdoses are up 22% in the wake of the pandemic. On Sep 1st 2020, Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) announced its own statewide “Naloxone Leave Behind Program.” According to MLive.com, MDHHS’ Director Robert Gordon, this is a way for “EMS providers to give Michigan families another resource to prevent overdose deaths.”

Michigan community programs can already request free boxes of naloxone from MDHHS. Soon, EMS programs in Michigan will be able to do the same for the purpose of leave behind programs. Roughly 66,396 total naloxone kits (or $4.98 million worth of naloxone) are available via Michigan’s naloxone portal for this fiscal year.

Over in Stark County, Ohio, overdoses are up 37%. According to CantonRep (Aug 30th 2020), The City of Canton, Stark’s County Seat, received a grant to provide 1,250 naloxone kits for area churches to distribute (especially in the Black community) and for local fire departments to leave behind with overdose patients who refuse to go to the hospital.

Plain Township Fire and Rescue Fire Chief Charles Shalenberger told CantonRep, “We’re in the business to save lives. We’re trying to offer them something they can use in an expedient fashion.”

In Tucson, Arizona, the fire department is piloting its own 'Leave Narcan Behind' program. According to KGUN9, this program was accelerated by a 250 percent increase of overdose patients who refused to go to the hospital for fear of being exposed to COVID-19. Like other towns, Tuscon’s naloxone kits will include information on local recovery services.

Over in La Crosse, Wisconsin, the Gundersen Tri-State Ambulance teams will be dispensing naloxone to overdose patients who refuse to go to the hospital starting in September 2020. Paramedics are also allowed to dispense a “Leave Behind Overdose Safety Kit” if opioid drug abuse is simply suspected, meaning people won’t have to nearly die to receive this life-saving antidote for future use.

According to Gundersen Emergency Services’ physician Chris Eberlein, MD, the local increase in overdose deaths is “due to the stressors associated with COVID-19 including economic factors, isolation and difficulty obtaining traditional mental health and addiction services.” In La Crosse as across the country, Dr. Eberlein also notes a heightened reluctance to visit a hospital due to fear of COVID-19 exposure.

In Pennsylvania, thanks to state health officer Dr. Rachel Levine’s 2018 standing order, EMS programs have been able to leave behind more than 2,400 doses of naloxone. In 2019, a pilot program equipped 112 people in a Philadelphia neighborhood with Narcan, and had them download an app where participants could submit and receive alerts about nearby overdose events. Throughout the year, nearly 3/4 of the participants responded to an overdose event, and in more than half of the responses, participants were able to administer naloxone 5 minutes before an ambulance arrived.

In Wilson County, North Carolina, another Leave Behind Program is set to launch soon. In addition to the Narcan first responders will leave, they will also hand off a small resource card that contains key recovery services. This card is tangible as well as symbolic for EMS Director Michael Cobb. “The opposite of addiction is connection,” Cobb told The Wilson Daily Times. “We just want to let them know that there are connections out there, and there are people who want to help you.”

In upstate New York, in Columbia County, where ambulance arrivals can take 9 minutes, their “Leave One Behind” program launched this past Thanksgiving. In neighboring Rensselaer County, in response to COVID-19 restrictions, residents can now text NARCAN to a shortcode to get curbside naloxone delivery, as well as fentanyl test strips. Anyone who texts can also subscribe to receive overdose spike alerts in the region, potentially alerting people to bad batches.

In Tennessee, Rutherford County is piloting yet another leave behind program with a focus on leaving naloxone with family and friends of people who’ve experienced overdoses, along with resources and a message of sincere care. Paramedic Joshua Crews told WGNS Radio, “It’s giving them a chance, instead of giving up on them.”

Other creative ways to make it rain naloxone are also on the rise. In West Virginia, the state just piloted its first Free Naloxone Day on Sep 2nd 2020, distributing over 1,000 naloxone kits across two counties. In Virginia, five regional health departments hosted free naloxone drive-thrus the first week of September. In Indiana, about two months into the pandemic, the state pulled together one million dollars for naloxone, to be distributed by a statewide nonprofit, so as to take some pressure off of over-taxed health departments.

By the end of 2020, overdose records will likely be broken by wide margins across the United States. Six months into the pandemic, the work now is to ensure the year’s worst losses are behind us.

Most fatal drug overdoses in the US involve opioids (70%) with some states like West Virginia seeing a higher ratio (75%). So it makes sense that cities, counties, and states from to Arizona, Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, & West Virginia are pushing new models like Leave Behind programs to blanket their communities with naloxone, the opioid overdose antidote.

How is your community mobilizing naloxone in new ways to save the most lives?